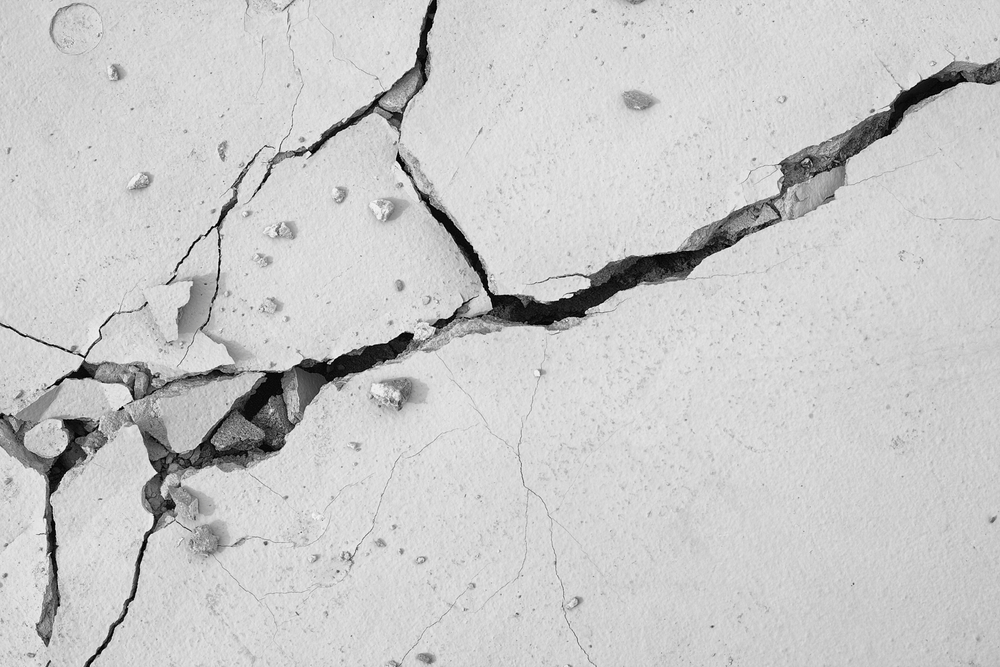

Since its use by the Romans in 150 BC, concrete has become the most popular building material in the world, but even after 2,000 years of use we have still found that all concrete eventually crack and usually lead up to a collapse of some kind.

“The problem with cracks in concrete is leakage,” says professor Henk Jonkers a microbiologist from Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. “If you have cracks, water comes through, in your basements, in a parking garage. Secondly, if this water gets to the steel reinforcements, in concrete we have all these steel rebars, if they corrode the structure collapses.”

That’s where Bioconcrete comes in. The bioconcrete is mixed just like regular concrete but Jonker’s has figured out the secret ingredient to take his concrete mixture to the next level.

“We have invented bioconcrete — that’s concrete that heals itself using bacteria,” says Jonkers.

Jonkers chose bacillus bacteria to use for concrete because of it thrives under alkaline conditions and the spores produced by bacillus bacteria can survive for decades without food or oxygen, making it the perfect choice for this project.

Jonkers started developing his plans for bioconcrete after a concrete technologist asked him if it would be possible to use bacteria to make self-healing concrete and after three years he solved the problem.

“You need bacteria that can survive the harsh environment of concrete,” says Jonkers. “It’s a rock-like, stone-like material, very dry.” The concrete must actually wait dormant for years before being activated by water.

“The next challenge was not only to have the bacteria active in concrete, but also to make them produce repair material for the concrete — and that is limestone,” explains Jonkers.

Calcium lactate is used to produce the limestone and acts as a food source for the bacilli bacteria. The bacteria and calcium lactate are set into capsules made from biodegradable plastic and are then added to the wet concrete mix.

When cracks start to form in the concrete, water gets through and opens up the capsules so that the bacteria can then multiply and feed on the lactate which combines the calcium with carbonate ions to form calcite, or limestone, that closes up the cracks.

“It is combining nature with construction materials,” says Jonkers, “Nature is supplying us a lot of functionality for free — in this case, limestone producing bacteria. If we can implement it in materials, we can really benefit from it, so I think it’s a really nice example of tying nature and the built environments together in one new concept.”